Remembering Peter

Ladefoged: Memorial

Service

| A memorial service for Peter Ladefoged was held at UCLA on Saturday,

4 Feb. 2006, at 2 pm, in the Humanities Conference Room in Royce Hall (Royce

314). It was sponsored by the Ladefoged family and the Linguistics

Department. Attendance was high, packing both Royce 314 and the adjacent

Royce 306, where closed-circuit television was installed.

The speakers, in order, were Tim Stowell, Thegn Ladefoged,

Katie (Ladefoged) Bottom, Shirley Forshee, John Ohala,

Ian Maddieson, Louis Goldstein, Sandy

Disner, Dani Byrd, Bruce Hayes,

Sun-Ah Jun, Sarah Dart, and

Pat Keating. A number of the speakers wrote

down their remarks and provided them to this site; click on their names to

go to the location below where their contributions appear.

Speakers: if you would like to contribute your words and I have been

unable to reach you, please send text or images to Bruce Hayes at

, or at Department of Linguistics, UCLA,

Los Angeles, CA 90095-1543. , or at Department of Linguistics, UCLA,

Los Angeles, CA 90095-1543.

|

|

Memorial Pamphlet

The Ladefoged family produced a memorial pamphlet which was distributed at

the service. You can download a copy here.

-

PDF format (single file,

whole document)

-

Original files: print on a color printer, then fold:

1 2

3 4

5 6

Thegn Ladefoged

I'd like to thank all of you for attending this celebration of my father's

life. Your presence here provides comfort to my family, and we thank you

for that.

I suppose many children idolize their parents and feel that they are or were

the most wonderful people in the world. I'm one of those children and feel

truly blessed that I have had my mom and dad as parents. They have always

provided their kids and grandchildren with a tremendous amount of support,

both material and emotional. From reading us Winnie the Pooh, to attending

my football games, to critiquing my manuscripts, Dad always gave my sisters

and I so much love. For me, one of the most special things about that

unconditional love and support is that it has continued to grow over the

years.

Besides giving me that love, my dad taught me a great many things. He taught

me humor and optimism. He also showed me how important it was to do things

that you have a passion for, and how you should try and excel at those things.

Perhaps more significant he also showed me how important it was to be a humble

person and accept your limitations. I remember when I was 8 or 9 and we lived

in Uganda. My sisters and I attended an American school and there was a sports

day. As most of you know, my father was not the most athletic (although he

was a pretty good boogie boarder), and at the sports day all of the fathers

were going to play a baseball game against the kids. It seemed as if my dad

was the only father who was not going to play in the game. My dad, knowing

that he was hopeless at running and catching balls, declined, and sat on

the sidelines and cheered with the mothers. I remember being really proud

of him that he was strong enough to be different; that he was secure enough

to cheer the success of the other fathers. Dad lived with that sense of

uniqueness and security throughout his life.

The most recent, but I dare say not the last, thing that dad has taught me

is how to die. In the last few years dad faced his own mortality with a sense

of peace and contentedness. He realized that he had lived a wonderful life,

and he hoped for more, but there seemed to be very few regrets or unfinished

tasks. It seems only fitting that Dad died quickly while returning from fieldwork

in India. While his death is horrible for many of us here, his life was truly

wonderful.

[top]

Katie Bottom

When I think of my Dad, three qualities come to mind: First, how laid back

he was, unflappable, my mother would say; second, his unflagging optimism;

and third, his great kindness. I know these qualities made him a wonderful

colleague, friend and husband. Trust me, they are exactly the attributes

you want in a father.

My family can tell you that I am not a very good driver. When I was fifteen

and first learning to drive, I was, well, worse. My father was the natural

choice to practice with me. He would sit back while we drove around the San

Fernando Valley for hours, never once appearing in any way nervous or alarmed.

As I would occasionally forget to stop, or back into a pole, he would remark,

“Never mind, dear. It doesn’t appear that any damage was done.

Lets just keep going.”

My favorite lecture of my fathers was a talk he gave to a Phi Beta Kappa

group back in 1989, entitled, “On Being Kind to Tortoises.” In

it, he posited the theory that he himself was a Tortoise as opposed to a

hare. He said that he had succeeded by finding something he liked doing and

then just sticking to it. By simply plodding along in life and developing

the thick shell of a tortoise, he said, he was able to overcome such setbacks

as being thrown out of high school for organizing a drinking club.

And I think it was his qualities of kindness, optimism and calm combined

with his instruction on being a tortoise, that allowed my sister, brother

and I to succeed in life. As we made our own mistakes, as we fumbled around

in life, he never once let us believe that we would do anything other than

succeed. He imbued in us a feeling of it just being a matter of finding that

one thing we each liked to do and then doing it. And in time, we each did.

We owe a lot of our happiness to our parents for that.

[top]

Louis

Goldstein

I want to remember some of the gifts that Peter has given us-his students,

his colleagues, the field of phonetics. One of these is the lab group and

lab meeting. Peter noted in his short autobiography, that it was never about

the equipment, but rather the people. And the lab group that sprang to life,

seemingly spontaneously, but actually under his careful guidance, provided

a way for those people to grow, to interact creatively and critically, to

support each other, and to make collective discoveries that none of us

individually could have made. (I do remember one time we seriously considered

submitting an ASA abstract under a pseudonym that would stand for the lab

as a whole). Even at the time, we marveled that the lab meetings were an

example of a wonderfully successful anarchy, that doesn't seem to work in

other, larger contexts, and we knew that it was Peter's hand behind the anarchy

that allowed it to work.

As those of us who had this moment in the sun spread out and created our

own labs, we brought that experience with us, attempted to imbue our own

groups with its spirit. In my own experience, it is never as successful as

the original, but it is there to some extent. And all of this makes the field

of phonetics a much better, more human place, than it would have been.

Other gifts. There are a variety of them, because in the Hollywood idiom,

Peter was more the Wizard of Oz than he was Henry Higgins. He discerned,

surely with help from Jenny, the prescriptions individuals needed to get

on with their lives and careers-courage, discipline, focus-and then dispensed

them with his own unique style. Sometimes what was needed was pretty basic.

For example, in the days (or rather nights) of swimming, the thought of exiting

from Peter and Jenny's superheated pool into the cool California night could

have been very daunting, but you knew that Peter would be there pouring glasses

of whiskey, and that made it possible to get out.

One of the gifts to me was an environment that gave me the courage to try

things without fear of failure. I recall the first time I had dinner at Peter

and Jenny's. Just before dinner, they asked for volunteers to carve the turkey.

No one spoke up; so I did. After suitably dismembering it, Peter asked where

I had learned to carve a turkey. "Never tried it before," I said.

He had a unique way of getting his point across, one that managed to be both

very incisive but still playful. When I described to him, during my first

year, an experiment I was in the process of doing, he compared it to trying

to sell a pair of shoelaces for a million dollars. I responded that, of course

I only needed to sell one pair. As it turned out, I sold my pair; the experiment

worked. But nonetheless I got his point about risky experiments.

In the course of dispensing what was needed, he was also able to make use

of clever strategies that he employed in his science. Late one night, a friend

and I sneaked into Peter and Jenny's pool for an unauthorized swim, emerging

undetected, so we thought. The next day while making a cappuccino (using

the aptly named "Atomic" machine that Peter and Jenny had donated to the

lab), Peter asked me if I had enjoyed my swim. "Very much," I replied, "how

did you know it was me?" "I didn't know," he said, "I've been asking that

same question to everyone."

Finally, I want to say something about my long-time friend and colleague,

Cathe Browman, who would very much want to be here but for her horrible illness,

and she wanted me to include her. Because of that illness, she has not been

able to show much emotion over the last several years. But when I told her

of Peter's death via video iChat (I have been out here for 2 weeks), she

was more animated than I had seen her in a very long time, and we cried together

connected by our computer screens (a use of communication technology Peter

would have appreciated; Cathe actually installed the first modem on the Phonetics

Lab computer and wrote the software for it). Both Peter and Jenny always

asked after her, and sent their love, and it meant a lot to her. And whatever

the merit of the research she and I were able to produce together, we could

never have done it without the gifts we received from Peter.

[top]

Sandra

Disner

The brilliance of Peter Ladefoged's accomplishments in the fields of laboratory

phonetics, linguistic theory and fieldwork, not to mention his widely-read

books and his acclaimed teaching methods and even his grand Hollywood adventure,

have tended to outshine his important contributions to the field of forensic

phonetics. But the latter touches the lives of all who stand accused, or

might someday stand accused, of a crime in which some crucial piece of evidence

is a voice - and this of course includes the innocent. Alas, such people

probably outnumber the linguists whose lives are touched by all of Peter's

other endeavors.

Back in the days, decades ago, when prosecution witnesses would earnestly

inform juries that they could identify a recorded voice with 99.6% accuracy,

Peter expressed skepticism. He was particularly provoked by the use of the

term "voiceprints" for "sound spectrograms", which falsely implies that these

are comparable to fingerprints. His clear-eyed evaluation of the methodology

employed by so-called "voiceprint examiners" - who, whether they wished to

admit it or not, were blending art and science -- and of the sorry realities

of forensic data (noisy body wires, slow tape recorders, the witness' set

of expectations) was considered by numerous appellate courts around the country,

and was cited in the reconsideration of the admissibility of such evidence

in a number of jurisdictions.

Peter designed several ingenious tests of the accuracy of speaker recognition,

including a multi-level study of familiar voices, with himself as subject

and his beloved Jenny as investigator. He was honest enough to note that

it took more than one sentence for him to recognize the voice of his own

mother (a not-uncommon anomaly; do YOU always recognize telephone voices

instantly?) and this admission was tossed back in his face by gleeful opposing

counsel for years thereafter.

But perhaps the most important, and certainly the most elegant, of Peter's

forensic studies was a two-page article in Language and Speech. It reported

that some of his own graduate students, all trained phoneticians and thoughtful

subjects, were misled by their expectations in a speaker-identification task.

Peter had inserted an unfamiliar African-American voice in a long string

of familiar voices from the UCLA Phonetics Lab group. Five of the seven

phonetician-subjects mistakenly identified it as that of an African-American

colleague of theirs, which would have completed the string of familiar voices.

The forensic implications of such a mistake, and the knowledge that even

trained phoneticians could be misled by expectations, were stunning. It raised

the same sort of doubts about guilt as were later raised by DNA testing.

Peter usually kept his academic and his expert witness personae quite separate,

but on the rare occasions when he had to go directly from classroom to court,

he turned a lot of heads. On those days Peter, who was usually clad in a

loose African tunic or a "best in division" 5K-run tee shirt, would show

up at UCLA in an elegantly tailored suit, crisp white shirt, and tasteful

gold tie. From the looks on his students' faces, he might as well have been

wearing a space suit, or a gorilla outfit. But for the eyebrows, he was

unrecognizable.

My own favorite anecdote about Peter's forensic work took place when he and

I played competing "experts" in the Trial Practice class at UCLA Law School.

He graciously offered to bring his laptop to the "trial" and share it with

me, so that I would only have to carry a floppy. What he didn't tell me was

that his laptop didn't have a floppy drive. So in front of the mock "jury"

I was left with no exhibits. (An obliging student was able to photocopy my

hardcopies, thank goodness.) Peter's sage advice to me afterwards was that

I should never take anything for granted, particularly when it comes from

opposing counsel. He referred to this as the time he "sandbagged Sandy",

but in fact the "jury" found for my side in that mock trial, most likely

out of sympathy for my plight.

[top]

Dani

Byrd

January 26, 2006

Dear Peter:

You always told us, your students, that if we could not express it in numbers,

our knowledge was “meager and unsatisfactory.” I believe that was

the quotation from Lord Kelvin, right? So, Peter, imagine my dilemma, sitting

here in a last effort to write something for you, but finding that I’m

wholly unable to be that clear and exact scientist you advised us to be.

I can count your books and articles but it would be saying very little because

it would not measure how they changed our field. I can count editions of

A Course in Phonetics, but how could I quantify the generations of scientists

that have been and will go on being taught phonetics as you defined it.

I can only poorly estimate the number of students that have sought out your

classroom…thousands, maybe tens of thousands. What an incredible blessing

that my own students, yet another generation, had the great fortune to be

taught by you these last two years! I, and uncountable other students, always

so wanted to please you, and you always did everything in your power to make

that possible. How many hours did you spend meeting with us making our work

better than it was before?

And how many days did you spend in the field with lovely people who put on

their finest clothing to honor your visit and educate the world via your

voice and your pen? I can’t begin to count the number of languages that

you brought to science—even Ian doesn’t know that. Would even Jenny

know the number of palatography-stained shirts? Or diet Cokes? Or waves caught?

I can only imagine the large number of people you and Jenny, very quietly,

helped through their most agonizing of personal crises. I don’t know

how to measure how warm your large hands were on mine in times of need or

how sure my heart was of your confidence and support. Is there some way to

measure the one-ness and mutual delight that was yours and Jenny’s together?

Actually, I wouldn’t wish to measure it at all; I know only that I aspire

to it for my husband and myself. When Oliver and I got married, you and Jenny

gave us, in addition to a wedding present, an elegant edition of A.A.

Milne’s The World of Pooh. I suppose today I should remember Winnie

the Pooh saying to Christopher Robin: “If there ever comes a day when

we can't be together keep me in your heart, I'll stay there forever.”

Peter, we weren’t ready for you to leave. Too many of us still have

data waiting to show you. Too many of us still need your advice. I fear that

I am failing you, somehow, here in our last conversation, that I simply cannot

reach your standard of sure quantification. But of this I am certain—you

will always be in my heart as my guide to being an honest scientist and being

a worthy friend and colleague.

I’ve also been thinking, Peter, that you might have been wrong about

needing numbers to satisfy. Oh, maybe it’s true that there is no way

to be other than “meager and unsatisfying” in saying a last goodbye.

But there are an uncountable number of us that know with all the sureness

in our hearts that we loved you, even if we can never tell you just how much

or number all the reasons why.

Love,

Dani

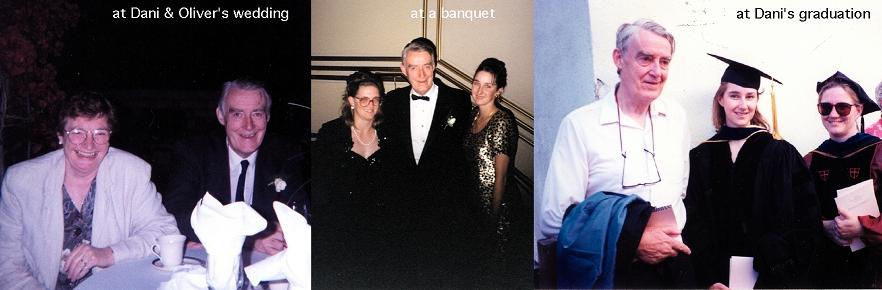

[full size version of above

image]

[top]

Bruce

Hayes

I came to UCLA Linguistics Department in 1981 as an Assistant Professor and

had the great good fortune to be assigned an office in the Phonetics Laboratory,

where I've stayed, ever since. So for much of the last 25 years, which is

about half of my life, I'd had the privilege of sharing Peter's company.

I'd like to begin my remarks by asking a silly question, which is why we

are gathered here together. The obvious answer is that in hard times it's

good to have your friends with you. But there another reason, too, I think--that

this is a very good opportunity to understand Peter better. We want to assimilate

in our memories the clearest, best picture of Peter we can, because for those

of us who knew him well this will be an important part of our store of memories,

for the rest of our lives. There's a lot to be said for recording as many

insights and idiosyncratic details as we can.

In your booklet you can find the web address for a page entitled

Remembering Peter Ladefoged (to which I continue

to invite people to contribute). On this page, you can find a fair number

of details about Peter, which I've enjoyed learning. My own little contribution

to this page focuses on Peter's impact on my own field of phonology, but

at the end I made it a little more personal, saying:

Peter brightened my day whenever he was here.

I'd like to try to pin this statement down a bit--why would a colleague

characteristically brighten my day?

I think that part of it is that Peter always created an aura of being

relaxed, in a cheerful sort of way. I could hear this in the low-key,

almost courtly language he used to address Jenny, or in his response to the

occasional crisis, where he kept things calm by keeping his voice down and

dipping into traditional British slang like "a bit thick". Peter's relaxed

persona was also evident in his intonational pattern, which, I would say,

was characteristically languid. If you'll go to the UCLA Phonetics Lab

archive, which was Peter's

last big project, you'll hear him starting off many recordings in just this

sort of intonation, essentially using his voice to set the native speaker

consultant at ease.

Related to this sense of relaxation, I think, is that Peter had a strong

sense of personal comfort, seen for instance in his self-reported practice

of writing books in the bathtub, or in bed surrounded by dogs.

Peter was an early enthusiast for laptop computers in part because, as many

of us can witness, they permitted him to do his writing in a posture that

looked like this:

and not like this:

All of this genial relaxation might have been a bit dull had it not be present

in someone who had such a lively mind. Peter always had something interesting

to say about any topic, and of course his professional research showed this

trait in spades: it made him a pioneer in so many areas. To mention a few,

there was the use of electromyography to monitor muscles in speech, the use

of inverse filtering to study phonation types, the transplantation of the

phonetics laboratory to the field, or--to go closer to my own area--the

theoretical concept of distinct articulatory and acoustic features.

|

|

In the end, I think the key trait behind Peter's persona was (just as

Katie said) optimism. Peter was fond of telling other professors that

he had been turned down for more grant money than anyone else he knew. At

first blush that sounds like an utterance of a self-pitying pessimist, but

in fact you have to take it in context--what Peter meant was that it was

by going out on a limb, repeatedly, that he managed to win more research

grants than any linguist ever had. In fact, I think that when Peter said

this, it was essentially a statement of pride in his own optimism. This is

the personal trait in Peter that I perhaps admire the most, and will do my

very best to remember. |

[top]

Sarah

Dart

Incredible as it seems now, when I started as a graduate student at UCLA

in 1981 I had never before used a computer. It was Peter who inadvertently

gave me my first experience manipulating a computer mouse. He called me into

his office to share something up on the tiny screen of his first Macintosh,

and, without any warning, I found I was supposed to click and drag something,

for the first time in my life. I did not put on a very good show-- arriving

too soon at the far edge of the mousepad, I was at a loss as to how to continue.

Rather than telling me what to do, Peter just waited quietly, watching my

struggles, until I had finally figured out that I could lift it off the pad

and start again where I left off. That was his way. He would lead us to the

questions and then watch over us without interfering until we arrived, on

our own, at the solutions. That is the sign of a true teacher.

As many have said, one of Peter's gifts was to involve students and colleagues

alike on an equal footing in the lab. Every week all the lab members would

sit in a circle in the lab and try together to figure out an unknown spectrogram.

The commentary would go around the circle and each person had to point out

something and make an educated guess on the value of one of the segments.

This could be rather stressful for us students as our turn approached, surrounded

by professors with much more experience. However, it turned out to be a wonderful

lesson on how professors could be fallible too-- making confident statements

like, "It's obviously an [m]" or "a classic velar" when, in fact, it turned

out to be nothing of the kind. Peter was never afraid to confess ignorance,

it was all part of the fun of learning.

But, for all his relaxed ways, Peter was always alert to his role as a teacher

and mentor. And this could sometimes come crashing right down on your head,

just when you least expected it. I remember once when we were all practicing

our talks for the upcoming Acoustical Society meeting. One of the students

had not prepared sufficiently and was bumbling around in an inconclusive

way. We were all stunned to silence when Peter said harshly, "If you can't

do any better than that, I will not allow you to give your presentation and

represent this lab." He would not let us shame ourselves with a mediocre

paper.

One of Peter's great strengths was his ability to keep focussed on the relevant

task at hand. His total disregard for the irrelevant, however, sometimes

went beyond what the rest of us could manage. I remember one day Peter came

to the lab meeting, sat down, put his feet up on a chair and began to speak

about the topic of the day-- a normal beginning to the meeting. However,

this time the informality had reached new heights (or depths) even for Peter.

The whole front half of one of his shoes was torn wide open and shredded,

with bits hanging down in all directions. And with his feet up it was just

a bit too close to eye-level for most of us to pretend we didn't notice.

At our curious glances he finally looked down absent-mindedly and said, oh

yes, the dog had eaten that one--- And went back to talking about the important

things.

When I read in Marie Huffman's contribution to the memorial webpage, about

her uneasiness when Peter told her that no one would believe a recommendation

unless it contained both criticism and praise, I decided I'd better look

back at the one he wrote for me, which my colleague had shared with me after

I was hired, (so I knew it couldn't have been that bad.) Well, Marie, you'll

be relieved to know that, unless there was something sinister in the rather

bland observation "She has a pleasant disposition that is very suitable in

a teacher," I think Peter's comment about criticism was just meant to keep

us on our toes with the uncertainty, making us aware that despite his loyal

support of us, he would also be constrained by truth and we'd better strive

to deserve that loyalty.

Another thing he said in that letter was a phrase that I'm willing to bet

he used in many, many of our recommendations. It is very characteristic of

both his humility and the egalitarian atmosphere that prevailed in the lab.

My version went like this: "It is always good when one of one's students

shows that what one has written in a textbook is plainly false! I am delighted

to learn from her." And I think that sums up Peter pretty well, he was delighted

to learn. And we were so fortunate to be able to learn from and with him.

Thank you Peter.

[top]

Sun-Ah

Jun

It is an honor to be given a chance to speak at this memorial service for

Peter Ladefoged. Like many others in the field, I was introduced to phonetics

through Peter's book A Course in Phonetics. I didn't know that the

saggital view of the handsome man in Chapter 1 was Peter Ladefoged until

I first saw him in early 90s at the Ohio State University Linguistics Department

colloquium. (It became clear that the man was Peter after I saw Thegn, Peter's

son. They really look alike!). At that time, I was excited to hear him speak,

but didn't have a chance to talk to him in person.

In 1993, when I came to UCLA to give a job talk for the position that opened

after Peter's retirement, Peter came to me after my talk, and with a smiling

face and resonating deep voice, he said he wanted to ask me some questions

and told me that I shouldn't worry about my answers because he was not a

voting member of the department. It was clear from my first personal encounter

with him that Peter has a great sense of humor and warmth that makes people

around him feel welcome and comfortable. A few months later, I met Peter

again at the Laboratory Phonology Conference in Oxford. It was after I had

accepted the job offer from UCLA. Peter introduced me to the people at the

conference by saying "She is me!". I was so honored to be introduced

that way. We were laughing when someone said how the IPA sound would change

if it's produced by a small vocal tract. I could never be like him, but I

will try my best. I just wish he could be with us for longer time so I could

show him how I am doing.

One of the few unforgettable experiences I have had at UCLA was to visit

Cheju Island, off the coast of Korea, to do fieldwork with Peter in 1998.

It was part of his endangered languages project. We spent two weeks in Cheju

Island, collecting data from the villages in the mountain area. But the island

was small enough for us to stay in the city at night and visit the village

in the daytime. Every evening, Peter was writing his book on his laptop computer

in the bathtub. He didn't seem to have any jet lag. He also had a good appetite,

but he was watching his diet. One evening, we were having dinner at the hotel

restaurant. When I ordered 'ome-rice' (fried rice omelet), he said that was

too high in cholesterol. He ordered some decent healthy food for himself.

After the meal, he wanted to have a diet Coke. So we walked around for a

few blocks and found diet Coke at a supermarket, but he didn't like it because

the sugar level was too high. I didn't know that the sugar level of diet

Coke differs from country to country. After searching for a real Diet Coke

for about five more blocks, he gave up and drank the 'sweet' diet Coke. I

thought that was the end of our dinner. Well, no! Peter asked me if he could

have some ice cream! Sure...he had a huge chocolate ice-cream with chocolate

topping! That was so Peter!

After our field work, we visited my hometown, and we both gave a talk at

my alma mater. That was a special moment in my life. The next day, Peter

wanted to meet my parents. My parents were of course very happy to meet him.

After finding out that my father is one year younger than him, Peter requested

my father to call him 'older brother' in Korean. Peter seemed to know that

age is very important in Korean culture. My father was delighted with Peter's

humor and impressed with Peter's humble, casual, and warm personality. …

Peter came to my office when he heard about my father's passing two years

ago and said he was truly sorry. I told Peter how great it is that he was

healthy, and he said he didn't do anything special. He just inherited a good

body from his parents. I truly believed that Peter would live many more years

to come.

I am a very lucky person to have been his colleague for the past 13 years.

He wouldn't know how much I was impressed with his scholarship and personality.

He was like a big tree providing shade and breeze to many people. He taught

me how I should live. I will try to be humble like him, warm like him, diligent

in writing like him, and be positive and optimistic like him. I will miss

him a lot.

[top]

Pat

Keating

Peter was the chair of both the search committee and the department when

I was hired in 1980, and of course once I arrived he was my closest colleague

and mentor. It's really hard to distill our 25 years together into a few

words. But I've used the occasion of speaking here today as a reason to review

what I've learned, or should have learned, from Peter. Some of these lessons

are trivial, some more profound, some of them - well, let's just say that

reasonable people can disagree about some of them.

The most profound is the one I am least able to talk about, and that's about

the phonetics lab. People who were here at different times have tried to

analyze, to put into words, what made the lab special to them. All I can

say today is that I hope that this part of Peter's legacy will continue strong

in his absence.

Peter was incredibly productive, so obviously he had a lot of wisdom to impart

about how to get work done (in addition to marrying Jenny, that is). His

pearls of wisdom include:

-

A related point: Try not to check email until afternoon, or even later, after

you've accomplished the more important business of the day (Peter once told

me, though this was years ago, that he tried to limit email to evenings if

at all possible).

Of course one element in Peter's productivity was his success in getting

external grants to fund his research. He had a couple of important lessons

about that, too:

Peter had a fair amount of advice to offer on preparing papers, posters,

and talks: explicit advice, such as --

-

Don't use sans serif fonts on posters; they are harder to read, and

-

Practice and time your talks before you give them (not followed on the present

occasion - his advice didn't cover how to keep from crying while practicing

your talk)

-

When writing a paper, first write as much of the whole paper as you can,

even before you have analyzed your data; then, before writing the final version

of the analysis section, first choose your figures, in order to decide how

you will present the data

-

I don't know how many of you have noticed this hallmark of Peter's writing,

but he did not believe in footnotes. He felt strongly that either the information

is needed, in which case it should be in the main text; or it's not needed.

In addition to such explicit advice that Peter gave as occasions arose, I

think we all learned one implicit lesson about giving talks, namely:

-

There is no such thing as too much cute multimedia in a talk - the more,

and the cuter, the better. How many of you remember him playing the song

"I get by with a little help from my friends" in his ICSLP keynote address?

Many others have commented on Peter's collegiality, which showed itself in

various ways, such as his founding and for years hosting the annual department

5K walk/run/swim/eat. I think I have distilled a few specific tips about

being a colleague:

-

Treat students as colleagues. There are lots of testimonials on the memorial

website about individual cases of this, but I'd like to point out a more

general and public instance: the strictly alphabetical listing of names of

lab members in Working Papers in Phonetics, with no indication of rank or

position, just all equal in our work After all, Peter said that it was the

class and hierarchical system in Britain that he was trying to leave behind,

and this must have been one of his first expressions of that sentiment.

-

Keep your office door open so that people can pop in with a question. Of

course Peter took this to extremes - he would leave his office door open

even when he wasn't there, with his computers in full view - sometimes I

would stand guard at his door until he came back.

-

Don't complain about having faculty meetings, because time together as a

group is very important, even if nothing concrete is accomplished.

Here's a very specific one that certainly made a big impression on me:

And one that is not specific to faculty, that I think has been ingrained

in the minds of most lab members over the years:

-

If you go somewhere on a trip, bring back chocolate for the lab, a local

specialty if possible, but bought at the airport if necessary.

There are a lot of these lessons that I still need to work on. I'll miss

having Peter as mentor and role model, and I'll miss showing him my future

personal improvement. But I'll also miss teasing him. For example, here's

something I'll miss: In his talks, Peter would quote Lord Kelvin for having

said "You do not really know anything until you can express it in terms of

numbers." And then I would pipe up, "But Peter,wasn't it also Lord Kelvin

who said "The radio has no future"?". Maybe I'll start quoting Lord Kelvin

in seminars just to see if someone else will take over my line.

It's hard to believe he's gone, isn't it? After his retirement, when Peter

would try to offer an opinion about running the lab or about course offerings

or anything else, Jenny would say "Peter, be quiet! You're history!" You're

history. And now he really is.

[top]

Back to Remembering Peter Ladefoged

Last modified February 5, 2006

, or at Department of Linguistics, UCLA,

Los Angeles, CA 90095-1543.

, or at Department of Linguistics, UCLA,

Los Angeles, CA 90095-1543.